By Leah Etling on November 18, 2014 in News

Drive out of Detroit’s Downtown and Midtown neighborhoods, away from the historic skyscrapers and abandoned ruins of once-grand buildings, and you are quickly amidst a whole different kind of surreal scene. Once densely packed with people, Detroit’s  outlying single family home neighborhoods have suffered immensely from the city’s ongoing depopulation.

outlying single family home neighborhoods have suffered immensely from the city’s ongoing depopulation.

Across the city’s 149 square miles, nearly every neighborhood had 15 percent of its homes abandoned or foreclosed. There are still an estimated 80,000 structures left standing. This summer, the federal government pushed Detroit to spend $850 million to tear down 40,000 of them in the long slogging war against blight.

Adam Hollier, Detroit native, Cornell graduate, and former City Council liaison for the Detroit Mayor’s office, sees the city’s sparsely peopled suburbs as an opportunity for change, and a new way of looking at urban life – one with plenty of open space.

Hollier’s new job isn’t in politics or real estate, but on Detroit’s vast urban prairie. Working for Hantz Farms, he leads a small team that planted 15,000 trees this summer in one of Detroit’s declining western neighborhoods. Hantz Farms purchased 1700 parcels, totaling 150 acres, from the city to create their “Woodlands,” where the grass and trash that covers houseless lots has been cleared. John Hantz, CEO and owner of Hantz Farms, lives in Indian Village, a historic neighborhood just a few streets away.

“What we’re doing clears the way so that other people can invest in the neighborhood. The goal is that that will bring other investment in housing or commercial real estate. It’s very similar to what Dan Gilbert is doing downtown, in that you know you’re throwing good money after good money,” Hollier explained.

The results of the clearing are impressive. From a lot that hasn’t yet been worked over, overgrown bushes spilled onto what would have once been a neighborhood street. Trash is everywhere – old tires, pieces of burnt wood, broken glass bottles. Five houses might now sit on a street where there were once 25, shoehorned into tiny 30’’ by 60’’ lots. It’s on the blocks where the debris has been cleared that the urban prairie really looks like a prairie.

“Now you can see four, five, six blocks in any direction,” Hollier pointed out “And if you don’t talk for two seconds it sounds like you’re in the country. Which is a really weird thing when you’re four miles from downtown.”

Over the next two summers, the Hantz team plans to plant an additional 30,000 trees. Some parcels may be used for farming – two ventures, growing mushrooms and hops – are in the planning stages.

Produce and jobs

Hantz Farms isn’t the only company working on new life for the urban prairie. Gary Wozniack is a man with a dream of repurposing 310 acres of vacant, city-owned land for high-yield agriculture, and simultaneously creating up to 700 jobs, most paying $10 an hour. It’s a 20 year plan that will begin in to ramp up with the first 25 acres over the next year.

The work would be suitable for employees with limited education and professional skills, including those who have done prison time or struggled with addiction, a type of opportunity that is sorely needed but rarely available in Detroit.

“We have a huge untrained labor force, probably upwards of 200,000 adults in the city,” said Wozniack, a native Detroiter and RecoveryParks President/CEO. This summer, the unemployment rate has hovered above 14 percent.

“We have a huge untrained labor force, probably upwards of 200,000 adults in the city,” said Wozniack, a native Detroiter and RecoveryParks President/CEO. This summer, the unemployment rate has hovered above 14 percent.

This fall, RecoveryPark expects to finalize its initial land deal with the city, purchasing the farm’s first 25 for just $1. The purchase will include the crumbling historic Chene-Ferry Market, an open air structure covered with trash that will become a headquarters for the operation.

The neighborhood where RecoveryPark will grow is even harder hit by abandonment than Hantz’ Woodlands blocks. It’s located on the city’s near east side, not far from the commercial New Center. But instead of 6 houses per block, here often only one or two remain. Without any mediation efforts , neighbors are left to cut the grass of dozens of empty lots or contend with trash and furniture dumped near their homes.

RecoveryPark won’t ask the remaining residents to live the area, but it will drastically change their neighborhood and bring jobs next door.

“When you drive through this neighborhood, because it’s so de-populated, we feel that if you bring 700 jobs here eventually the housing developers are going to come along. And after the housing is built, the commercial strip mall people will see there’s jobs here, housing here, maybe people need a place to buy chips,” Wozniack said.

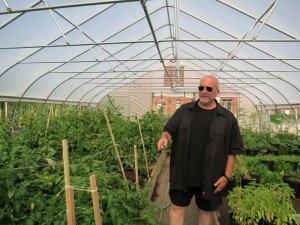

Much of the farming operations will be housed in greenhouses and plastic-covered high tunnels, which are suitable for growing delicious healthy produce year round. The plan is to distribute to restaurants and grocers within a 300 mile radius, ensuring that food can get from the farm to its ultimate destination – the dinner table – in less than 24 hours.

Hantz and Wozniak’s projects on the prairie are two of the larger scale examples of how Detroit is putting its vast open spaces to new use. Community gardens are also popping up, some to feed the hungry and homeless, others simply to feed the neighborhood. Grocery shopping options are limited in the neighborhoods hardest hit by home abandonment.

John Mogk, a law professor at Wayne State University who is involved with the city’s master planning efforts, says it took two years to get Detroit city zoning changed so that agriculture operations were possible in the city limits. He’s excited to see urban agriculture coming online, but says that so far, the small community gardens – counted at 1400 and growing — are just scratching the surface.

“We have 40 square miles of vacant land in Detroit,” Mogk explained. The city’s new master plan, which will be completed in 2015, is expected to expand land use opportunities for a prairie that was never part of anyone’s urban plan.

Editor’s note: Second in a series. Read the first article on the Motor City’s Second Act here.